How 10 Women Liberated this City from Police & Drug Lords!

On the morning of April 15, 2011, a group of about 10 P’urhepecha native women from Cheran, Michoacan, Mexico, detained one of the hundreds of trucks that passed through Cheran every day, transporting wood stolen from the community’s forests.

The men in the trucks were invariably armed to the teeth and today was no exception.

The forests of Tres Equinas, Pakarakua, San Miguel, Cerritos El Cuates, Carichero, Cerrito De Leon,Patanciro and El Cerecito, from which the wood was taken, belonged to the people of Cheran, but people who brought that up to these bandits were humiliated insulted and threatened until they were silent. If they would not be silent, they were murdered.

The bandits also took what they wanted from the local women, but when these crimes were reported to the local authorities, they were met with complicit Indifference. It had been that way for years. It did not matter the charge. Rape, Kidnapping, Assault, Robbery, even murder. The local authorities did nothing, because the bandits paid better and were far more intimidating then the people of Cheran. Or so they thought.

Sexual assault of the local women was a daily occurrence. Rosa, a 34 year old woman from Cheran, and one of 10 women who stopped the truck said that when the bandits passed her in town, they would say “Soon, we will run out of timber to take. But there is more for us than timber in Cheran. There are the women. And there are still plenty of women for us to take.”

Something had to be done, so these ten women stopped the truck, and with it a piece of heavy cutting equipment coming down from the forests. They intercepted the vehicles at corner of Avenida Allende and Avenida Dieciocho de marzo.

They had no grand plan, no guns,not even any vehicles with which to block the road. Just 10 women, standing in the way. 10 women willing to say “No!” Wives and mothers, daughters and sisters, with nothing to protect them against the bandits guns. In a matter of seconds, they could have been mowed down, their blood mingled with the dirt, and their families left grieving. But that is not what happened.

“We just stopped the cars.” Says Rosa. “It was scary, but at the same time we were firm in the confidence that we were doing what needed done. We could not let things stay the way they were.” The people of Cheran saw what was happening, and their courage emboldened others. More men and women joined in. The bandits tried to to jam the truck into gear and force through,

“…And we pushed back. We felt the swell of courage, but we were still a little afraid. We pulled the men from the cabin truck, We decided to take a stand!”

By that afternoon, most of the towns 18,000 people had gathered: Around fires, in groups in their neighborhoods, outside their homes on the same streets they hardly dared walk earlier the same day, for fear of the terror wrought by organized crime and complicit local officials. They had expelled the bandits. No one had been killed or maimed, but the bandits were warned firmly to not return. Cheran was theirs again.

In the local native language Cheran meant “to frighten” and in their neighborhoods and around their campfires spoke of their fears. They talked about the panic that they would feel when the alarms were sounded. When the Bandits returned. Everyone knew they would return. By the fires, they shared their fear, their anger, along with their coffee and tea, their Mezcal and their food.

Over that dinner, they rediscovered their dignity. And with it came their courage. The bandits would be back. That did not matter. The government would not easily let them be free. That did not matter, either. They had stood once, unprepared and afraid, because ten women said no. They would stand again, but they would be prepared, they would be courageous, and they would be far, far more than ten.

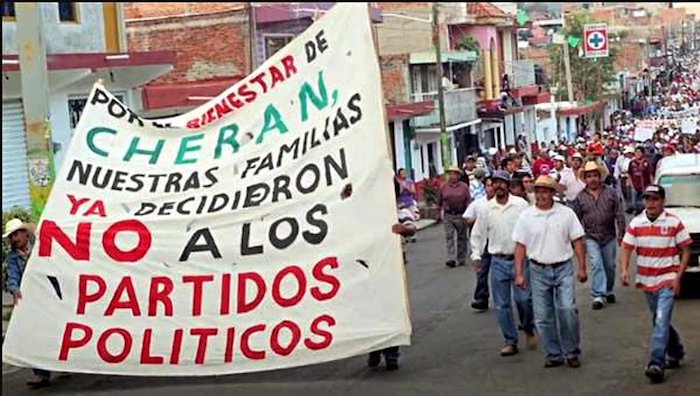

In the next few weeks, they expelled the equipment the bandits used. It was returned to the thieves who owned it. The problem was, the local government and the police sided with the bandits. That could not be tolerated, so they threw them out of office, and in their place established their own government, local and small, governing at the will of the people. The bandits and their government lackies sued.

Cheran fought back. By the 2012 election, the supreme court of Mexico agreed. Under article 39 of the Constitution of The United Mexican States, the people of Cheran had every right to govern themselves, by their own customs. In Cheran, they placed 150 bonfires, gathering places for political discourse.

Everyone had a right to come and be heard, and each campfire served only about 120 people. By a series of public votes, they chose a council of 12 people, called the Keri. The Keri have no authority to make law. That is done at the bonfires. The Keri simply carry out the decisions made at those bonfires. At any time, the people assembled, can by vote, remove the power of the Keri.

As a result of this system, Cheran did not participate in the last 2 federal elections in Mexico, in 2012 and 2015.The town was not filled with the propaganda and compromises, with the bribes and false promises that political parties thrive on. However, in 2015, Cheran elected its second Keri, 5 years after they won their freedom.

They still face countless challenges within, and mounting pressure from outside. In spite of all that, and whatever happens, they have demonstrated a policy very different from the ones that have drowned Mexico in blood. From the very beginning, the entire idea has been met with skepticism, and sometimes hostility and disdain, from the elite.

How can a small indigeoneous community defy the limits set by big government, political parties, corporate media, big business? “It is impossible for Cheran to last” they said. Now, years later they say “It is impossible for Cheran to survive.”

Perhaps it is as impossible as 10 women facing down a truck full of men with AK-47s. But it is not as impossible as anything good coming from politics as they are. But what if? What if they keep doing what is called “Impossible.”

What if their system, in spite of the doom and gloom of politicians and analysts, keeps working? What if words like Justice, Truth, Dignity and Community are more than fantasy?

As of April 15, 2017, Cheran celebrates 6 years of independence. Surely it really is impossible not to congratulate them! Happy Anniversary!

Thanks to Ruptura Colectiva and Ramon Olmedo, our sources for this story.

_____

Below is the text in Spanish, that this story was largely translated from.

“Una política de emancipación radical no se origina en una prueba de posibilidad que el examen del mundo subministraría.” Alain Badiou, Condiciones, p. 210

La mañana del 15 de abril del 2011, un grupo de alrededor de 10 mujeres del municipio p’urhépecha de Cherán, Michoacán, detuvieron a una de las centenas de camionetas que todos los días cruzaban el pueblo para transportar madera robada de los bosques de la comunidad.

Las camionetas siempre iban tripuladas por hombres armados hasta los dientes.

Desde al menos el 2008, los criminales no sólo habían arrasado los bosques cercanos de Tres esquinas, Pakárakua, San Miguel, Cerritos los Cuates, Carichero, Cerrito de León, Patanciro y El Cerecito, sino que asesinaron, insultaron, humillaron y amenazaron a cualquiera que insinuara un reclamo. Al parecer, también violaron a varias jovencitas. Las múltiples denuncias de la comunidad naufragaron por años en un valle de silencio e indiferencia en las oficinas de gobierno. En general, la agresión sexual a las mujeres del lugar era pan de todos los días.

Rosa , una cheranense de 34 años de edad, cuenta con los ojos y las mejillas a punto de reventar: “Ya cada que pasaba, decían: ya se va a acabar la madera; pero seguimos con las viejas de aquí de Cherán, decían.”

Rosa fue parte del grupo de mujeres que detuvo a la camioneta mencionada en la esquina de Allende y 18 de Marzo, cerca de la Iglesia del Calvario, en el Barrio Tercero de Cherán. Esas mujeres no usaron ningún camión o auto para cerrar el paso a los talamontes. Tampoco recolectaron armas previamente ni planearon una emboscada. Ni siquiera se pusieron de acuerdo un día antes. Los únicos vehículos con que se enfrentaron a los criminales fueron sus cuerpos.

Los suyos eran cuerpos hechos de los mismos átomos que los de los demás: con los mismos tejidos, las mismas cicatrices, las mismas asimetrías de carne, las mismas redondeces, los mismos granos, los mismos excesos. Es decir, en principio, cuerpos como cualquier otro y como ningún otro. La verdad es que frente a ese grupo de hombres armados, los cuerpos de esas mujeres eran cuerpos que pudieron terminar baleados en cuestión de segundos. Ahí hubieran quedado los huérfanos, los viudos, las madres con las lágrimas rebotando en los regazos. Por fortuna no fue así.

Aunque después se sumaron los jóvenes y el pueblo entero, el horizonte para transformar la realidad se constituyó, al menos en los momentos iniciales, por un manojo de cuerpos de mujer: cuerpos quebrantables, precarios, vulnerables, en perpetuo riesgo de perderse en el abismo de la muerte. Cuerpos que en ningún momento perdieron el miedo; tampoco la rabia, la ira, el coraje necesario para transformar su mundo.

Como dice Rosa: “Nomás detuvimos los carros. Se daba miedo. Pero al mismo tiempo se daba miedo y coraje de que no podíamos hacer otra cosa más que de echarle ganas. Los señores trataban de aventar el carro así. Pues el carro así pa’rriba. Se levantaba como parándose de llantas. Y nosotros pus lo parábamos. Era mucho coraje […] pero teníamos un como temorcito dentro del corazón. […] Se decide uno a levantarse porque ya no le importa a uno el coraje, y así pues.”

Ese 15 de abril por la tarde, la mayor parte de los 18,000 habitantes del pueblo se reunió alrededor de fogatas que instalaron en sus barrios, en sus esquinas, afuera de sus casas. En esas mismas calles de las que habían sido expulsados por la complicidad del crimen organizado y el gobierno local.

Cherán en p’urhépecha significa asustar. Los habitantes de este pueblo descubrieron que en esas fogatas podían no sólo compartir el susto, el miedo, el pánico cada vez que las alarmas anunciaban que regresaban “los malos”. Ahí, junto a las llamas protectoras, también compartieron la ira, el café, la dignidad, el té de nuriten, el mezcal, el amargo y la cena.

En las primeras semanas del movimiento, expulsaron a los talamontes ilegales, a la policía coludida con el crimen, al presidente municipal y a todos los partidos políticos. El pueblo entero se organizó en una forma de democracia innovadora que desde entonces se concentra en la participación directa en unas 150 fogatas instaladas a lo largo y ancho de la comunidad. La Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación aprobó una controversia constitucional que permite a Cherán regirse por sus usos y costumbres.

Eligieron, en voto público, un concejo mayor formado por 12 notables llamados Keri (grandes). Todos ellos propuestos primero en sus fogatas, elegidos en sus asambleas de barrio y designados por la asamblea general. La mayor grandeza de estos Keri es que no son autoridades. Como lo explican con orgullo los habitantes de Cherán: al interior de la comunidad “los Keri son sólo representantes; la única autoridad es la asamblea”.

Lo que esto significa de manera práctica es que los Keri sólo pueden ejecutar las decisiones que se toman en fogatas y asambleas y pueden ser relevados de su puesto en cualquier momento que la asamblea lo decida. Algo bien distinto a lo que pasa con el resto de los representantes del país.

Como resultado de esta nueva política, Cherán no participó en las elecciones federales del 2012 y 2015. El pueblo no se llenó de propaganda ni de las componendas, sobornos y promesas con las que todos los partidos políticos de este país operan. En mayo del 2015, Cherán eligió, por usos y costumbres, su segundo Concejo Mayor. A la distancia de cinco años, la comunidad enfrenta un sinnúmero de desafíos al interior y de presiones continuas del exterior. Sin embargo, pase lo que pase, el municipio de Cherán ha dado testimonio de cómo crear una política muy distinta a la que tiene a este país ahogado en sangre.

No obstante, desde el comienzo del movimiento y hasta la fecha, la mayor parte de los analistas, estudiosos y políticos han mostrado escepticismo, cuando no hostilidad y desdén, hacia el proceso que se lleva a cabo en Cherán. Para muchos, es imposible que una pequeña comunidad p’urhépecha despliegue de manera duradera una política que desafía los límites establecidos por las instituciones gubernamentales, los partidos políticos, los medios de comunicación y las empresas. “Es imposible que Cherán dure”, dijeron muchos hace cinco años. “Es imposible que Cherán sobreviva”, dicen muchos cinco años después.

Es tan imposible como que 10 mujeres detengan a un doble rodado tripulado por un comando de criminales armados con AK47; tan imposible como que los huicholes detengan el avance de las mineras canadienses en Wirikuta; tan imposible como que los zapatistas existan desde hace más de 30 años; tan imposible como que la política signifique algo más que la tragedia con que se gobierna a este país. Quizá la política, al menos la política como se practica en Cherán, sea justo eso: una especie de compromiso con la imposibilidad.

La política como una suerte de alfarería de lo imposible; como un telar en el que ?a contrapelo de lo que nos dictan los partidos políticos, las instituciones y los gobiernos? se teje un rebozo imposible que atraviesa y cobija a todos los que participan en ella. O quizás esta política sea como una máquina sin poleas ni engranes en la que se fabrican palabras imposibles como justicia, verdad, dignidad o comunidad; palabras que se afirman como posibilidades a partir de los despojos de la imposibilidad. Este 15 de abril del 2017 se cumplen 6 años de imposibilidad en Cherán.

Imposible no felicitarlos: Feliz aniversario.